With the opening rounds of the 2025 Formula 1 World Championship having recently taken place, this is an appropriate moment to recount a story from the School’s motor racing history. Bloxham lies firmly in the UK’s ‘Motorsport Valley’, with the homes of six Formula 1 teams within an hour’s drive from the School: Mercedes (Brackley), Alpine (Enstone), Aston Martin (Silverstone), Red Bull (Milton Keynes) and Williams (Grove), as well as the circuit at Silverstone, home of the British Grand Prix. A sixth team, Haas, have their forward base in Banbury, which is also home to Prodrive, a major name in many forms of motorsport, which was founded by former Bloxham School parent, Dave Richards. A number of Bloxham pupils have made their name in the sport, including Will Bratt (LS Sy 99-07) in F2 and GP2 and Jonny Wilkinson (Sy 17-22) in Ginetta GT5 and F3, while still a pupil at the school. Tom Pringle (Cr 18-22) and Oliver Marçais (Sy 16-21) have also recently been spotted out on the track.

Perhaps the most illustrious name in the school’s motor racing history, though little known today, is that of Alex Mosses, a pioneering figure who was present at some of the key moments in the evolution of the sport and took part in the notorious race which almost killed it off three years before the first Grand Prix took place. Alex Mosses was born on 4 June 1875 and attended Bloxham between September 1887 and December 1892. At school he developed a passion for engineering – Bloxham was unusual among Victorian public schools in its encouragement of practical subjects – and after Bloxham he worked for a firm of naval engineers before getting involved in Britain’s nascent automobile industry.

In October 1902 he entered the series of trials run by the Automobile Club for motor-car tyres, with a prize for the first car to complete a distance of 4,000 miles, He won the prize with a 12 h.p. Panhard, fitted with Dunlop tyres. This was the same car in which he and Helen, his new wife, set off for their honeymoon following their wedding the same year.

The following year he helped another young driver, Charles Rolls, in his quest to set a land speed record. Mosses was the mechanic for Rolls’ car, a French-made 80 h.p. Mors, when he was timed at 133.25 kph (82.8 mph) for a flying kilometre at Clipstone Park. While Rolls went on to set up his historic partnership with Frederick Royce, Mosses moved to Napier’s, one of the burgeoning number of small companies seeking to establish themselves in the new automobile industry.

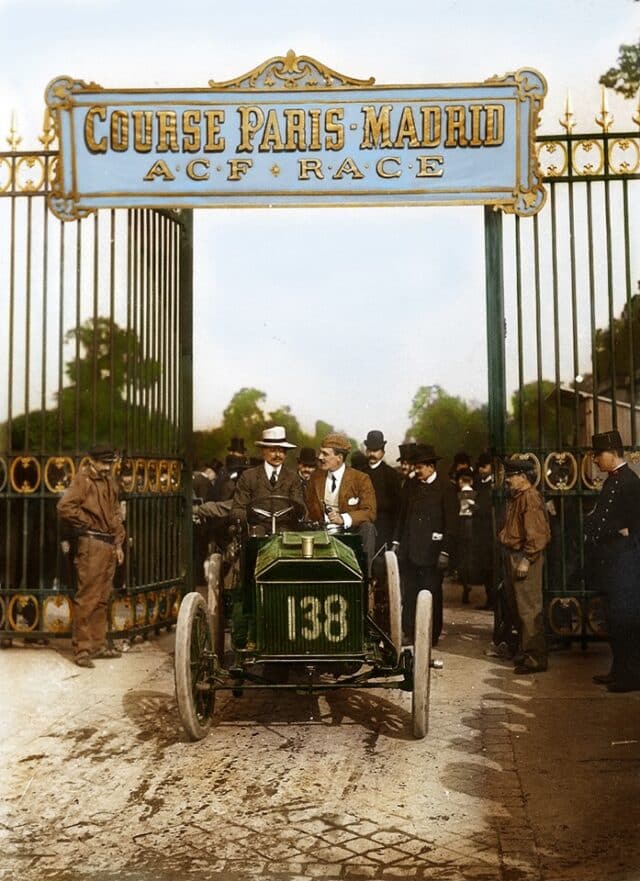

Owner Montague Napier saw racing as the ideal way to market their cars and to boost the British automobile industry, which trailed in the wake of French manufacturers. For the 1903 Paris to Madrid race, the company entered several of their 35 h.p. cars (which actually delivered approximately 45 brake horsepower). The Napier had a capacity of 6.5 litres and a top speed of 130 kph (81.3mph) and was clad in a green livery which was the origin of the term British Racing Green.

As an experienced engineer, Alex Mosses was chosen by Napier to be the passenger and riding mechanic in the car, which would be driven by Colonel Mark Mayhew, who had previously driven for Peugeot. The organisers attracted an enormous entry of 224 vehicles for the race, which was the biggest and most important since the development of the motor car. The competitors included entries from Renault, Mercédès and Fiat alongside the pre-race favourites, the most powerful cars, Napiers and de Dietrichs (the latter the work of the brilliant young Italian designer Ettore Bugatti). According to Scientific American, ‘Never before has there been shown a greater interest on the part of the public in an automobile race, and it is estimated that at least two million persons were ranged along the route at different points between Paris and Bordeaux.’

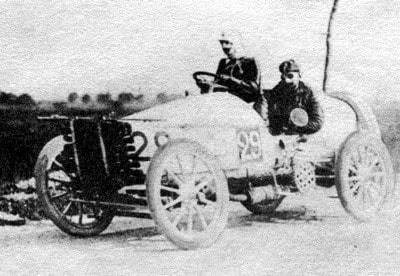

Early on the morning of 24 May 1903, the cars set off from Versailles at one-minute intervals on the first of three stages, to Bordeaux, but it soon became clear that the size and unruliness of the crowds, the state of French country roads and the high speeds of which some of the cars were capable (up to 140kph – 87.5mph), made for a lethal mixture. Charles Jarrott, the first driver to set off, later recalled that ‘…it seemed impossible that my swaying, bounding car could miss the reckless spectators….I tried slowing down, but quickly realised that the danger was as great at forty miles an hour as at eighty. It merely meant that the crowd waited a longer time on the road.’

At Poitiers, roughly halfway to Bordeaux, Louis Renault was leading with De Knyff and Jarrott in their de Dietrichs second and third, while Marcel Renault was gaining rapidly. Mayhew and Mosses were up with the leaders but came to grief within sight of the finish for the day. According to The Daily Mail, ‘Mayhew, who was driving, noticed the front wheels spreading apart, and the steering gear became uncontrollable. Mr Mosses jumped, turned several somersaults, and was only bruised and dazed. The car headed for a tree. Mr Mayhew put on the full break force but nevertheless received a severe shock.’

Mayhew suffered severe bruising to his ribs and cuts to his leg but counted himself fortunate to escape serious injury or worse. It was later determined that the cause of the crash had been a flaw in the metal of one of the steering connections. Mosses wrote to his wife the next day to reassure her:

‘We were doing splendidly, but after about 300 miles, in rounding a corner, the steering gave out, and we were violently thrown against a tree. Seeing what was coming, I instinctively jumped, and by so doing probably saved my life. I turned a couple of somersaults, and, on regaining my feet, saw Mark was badly knocked about in the chest region, and had a nasty gash in his leg. I gave him brandy and sucked the wound in his leg, and got him to Bordeaux eventually. I am quite unhurt, except for a slightly sprained wrist, and a nasty graze on my knee.’

On arrival at Bordeaux, Alex Mosses gradually became aware of the carnage that had unfolded among the rest of the field. Only 99 cars survived the first of the three stages. A total of five drivers had been fatally injured in crashes, some involving spectators, three of whom were also killed. The only female competitor, Camille du Gast, was in 8th place when she stopped to rescue another driver, who was trapped underneath his vehicle; she saved his life but ended the day in 45th position. The most famous victim of what would later be dubbed ‘The Race to Death’ was Marcel Renault, who crashed into a ditch and suffered fatal head injuries. A Renault would win the very first Grand Prix, the French, three years later, and Marcel’s brother Louis would go on to make Renault the biggest car manufacturer in France.

The immediate outcry at the carnage was such that the race was abandoned and motor racing on public highways was banned. Some politicians called for an outright ban on motorsport, but most accepted that the pressing need was for racing to take place on circuits, where the crowds could be kept away from the cars.

As for Alex Mosses, he decided that Paris-Madrid marked the end of his racing career: ‘I enjoyed it greatly, but do not feel inclined for any more racing after this.’ He became the chief test driver for Dunlop and spent the rest of his life in the motor car industry, dying in 1951. In his later years he could look back on a life in which he had played his part at a pivotal age for the automobile in general and motor racing in particular. When he drove his first car the sport was in its infancy, but by the time of his death, the Formula 1 World Championship was in its second year and the age of Ascari and Fangio, Alfa Romeo and Ferrari had arrived.